In a remarkable speech in praise of lying, the comedian known as Bruscambille proves that deceit is better than truth. For instance, the beautiful widow Judith saved her nation through her lies when she seduced Holofernes, the Assyrian general, before beheading him. Similarly,

if someone had killed his enemy in a secret place, and he was arrested by the authorities, would he wish to confess his crime? In just the same way, if someone were accused of having made some droning music from the depths of his trousers, would he also wish to confess it for his honour? Would he not take the highway to Denial Town?

[si quelqu’un avoit tué son ennemy en lieu secret, & qu’il fust apprehendé de la Justice, le voudroit-il confesser? Tout de mesme si quelqu’un estoit accusé d’avoir fait quelque Musique en faux bourdon au fonds de ses chausses, le voudroit-il confesser aussi pour son honneur? Ne prendroit-il pas le grand chemin de Nyort?]

The great lexicographer Randle Cotgrave translates ‘faux bourdon’ as ‘the drone of a bagpipe’. In case we were in any doubt about the meaning of the expression ‘faux bourdon au fonds de ses chausses’, the royal interpreter Antoine Oudin, who in 1640 published a dictionary of French ‘curiosities’, many of which he drew from his careful reading of Bruscambille, defines it as a ‘big old fart’ (‘un bon gros pet’).

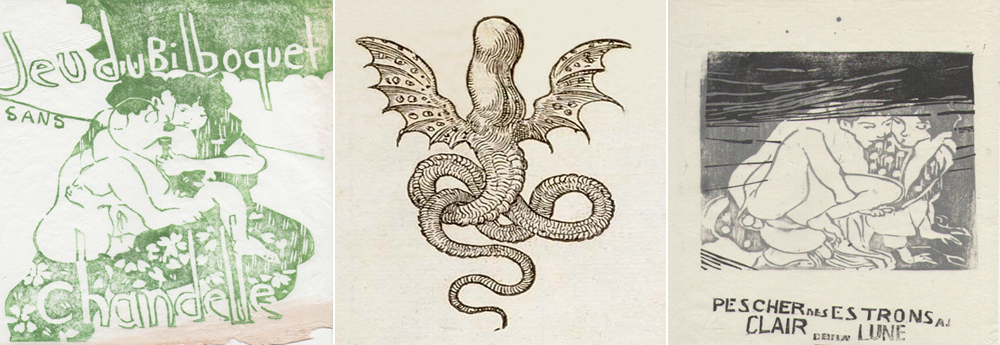

The bagpipe-droning fart has reappeared in one of Dominic Hills’s recent prints:

The techniques of Japanese print-making practised by Dominic Hills are more complex than they might appear at first sight. Similarly, it might be tempting to dismiss Bruscambille’s humour as puerile, but that would miss the point of how he puts together his speech to set up all kinds of comic contrasts, equating denying a murder charge with pretending not to have farted, alongside precise references to Plato and Aristotle, among others. The seventeenth-century audience would have loved all this, and the persuasive ingenuity involved in naughtily demonstrating that lying is preferable to the truth. But just in case we were tempted to take any of this too seriously, Bruscambille immediately follows his speech praising lying with one eulogizing truth. Whether it is better or not to admit to making the sound of a droning bagpipe in the depths of one’s trousers remains, therefore, an open question.