In the nonsensical court case between the lords Baisecul and Humevesne (Kissebreech and Suckfist), in Rabelais’s Pantagruel (1532) the latter makes the following statement in the wonderfully evocative translation by Sir Thomas Urquhart:

If any poor creature go to the stoves to illuminate his muzzle with a cowsherd or to buy winter-boots, and that the sergeants passing by, or those of the watch, happen to receive the decoction of a clyster or the fecal matter of a close-stool upon their rustling-wrangling-clutter-keeping masterships, should any because of that make bold to clip the shillings and testers and fry the wooden dishes? Sometimes, when we think one thing, God does another; and when the sun is wholly set all beasts are in the shade. Let me never be believed again, if I do not gallantly prove it by several people who have seen the light of the day.

The emboldened phrase is one of several plays on words, which is clearer in the original French:

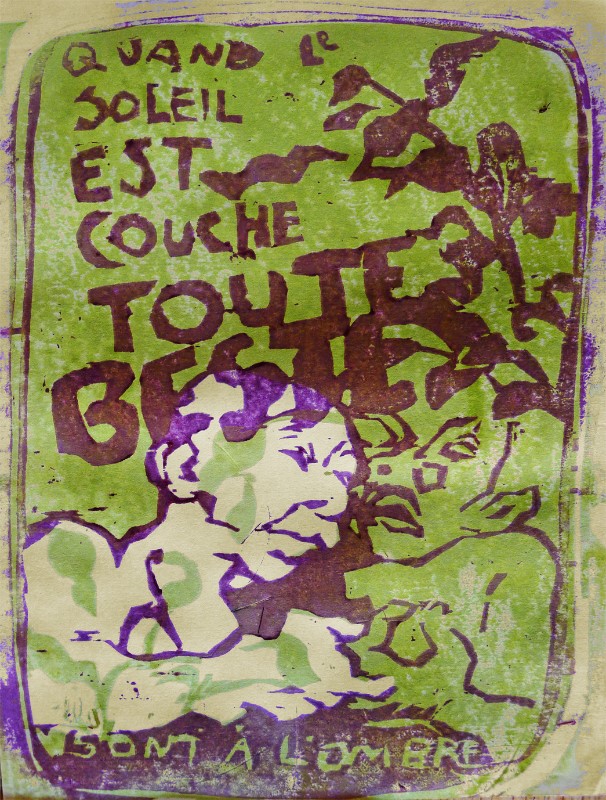

Quand le soleil est couché, toutes bestes sont à l’ombre

It’s a joke on the ambiguity of beste, which means either beast or idiot (or, better, one of Randle Cotgrave’s translations, including sot, doult, loobie, blockhead). In other words, it’s a blink-and-you-miss-it insult hidden within the gibberish. It implies of course that we are all loobies and, incidentally, that the Lord of Suckfist will struggle to find ‘people who have seen the light of the day’ – we as readers are in the dark about what he and the Lord of Kissebreech are debating so animatedly yet ludicrously.

I mentioned this expression to Dominic Hills recently, as I was about to discuss it at a research seminar at the Sorbonne. He rapidly produced a print inspired by the beasts/idiots, which happily I was able to project during my talk:

Subsequently it emerged that the shaded monsters/loobies are inspired by Goya, the whole effect by Ver sacrum, the green and purple shades by a plant, and so forth, a whole soup of influences of which Rabelais would have approved.

Working on such research, talking nonsense at the Sorbonne means being in the shade, of course. Dominic Hills’s print reminds us of Rabelais’s original creativity, not to mention nonsense, and thereby helps take us back into the light of day.