In his speech in praise of the number three, the four-hundred year-old French comedian known as Bruscambille notes:

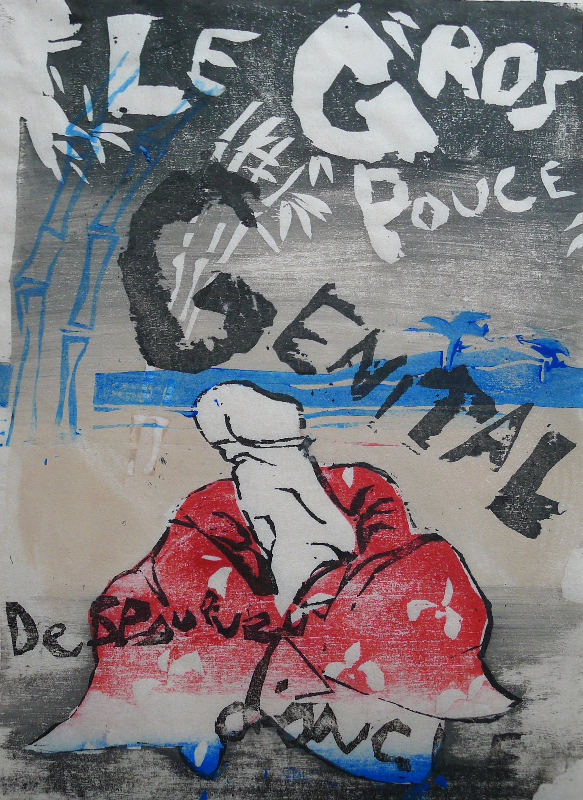

doesn’t a man have seven times three fingers, i.e. ten on the hands, ten on the feet, and the big genital thumb, which even if lacking a nail, nevertheless does more duty than all the others put together, because in a single blow that he strikes on nature’s anvil, sometimes he makes a great captain, sometimes a coward, sometimes a Braggadochio, sometimes an attorney, sometimes a merchant, sometimes an officer of the court, sometimes a witness, or even less, sometimes a pimp, sometimes a kitchen boy, sometimes a footman, and so on and so forth, Nature in truth has been a little harsh as far as he’s concerned because not content with having made him without a nail, she has also made him one-eyed, albeit that in compensation she has doted him with such clarity of vision that when he wants to meditate and rifle through the secrets of nature, he has no need of glasses nor of a candle to find the chamber, the wily fellow like a good blood-hound knows where the hare is hiding, allowing him to complete his commission, and what makes him welcome among ladies is that he lives without pride and ambition, his flight is not too high, in fact all his aims are only towards the mid and single point, he only ever wishes to lodge in a small, narrow and tight space.

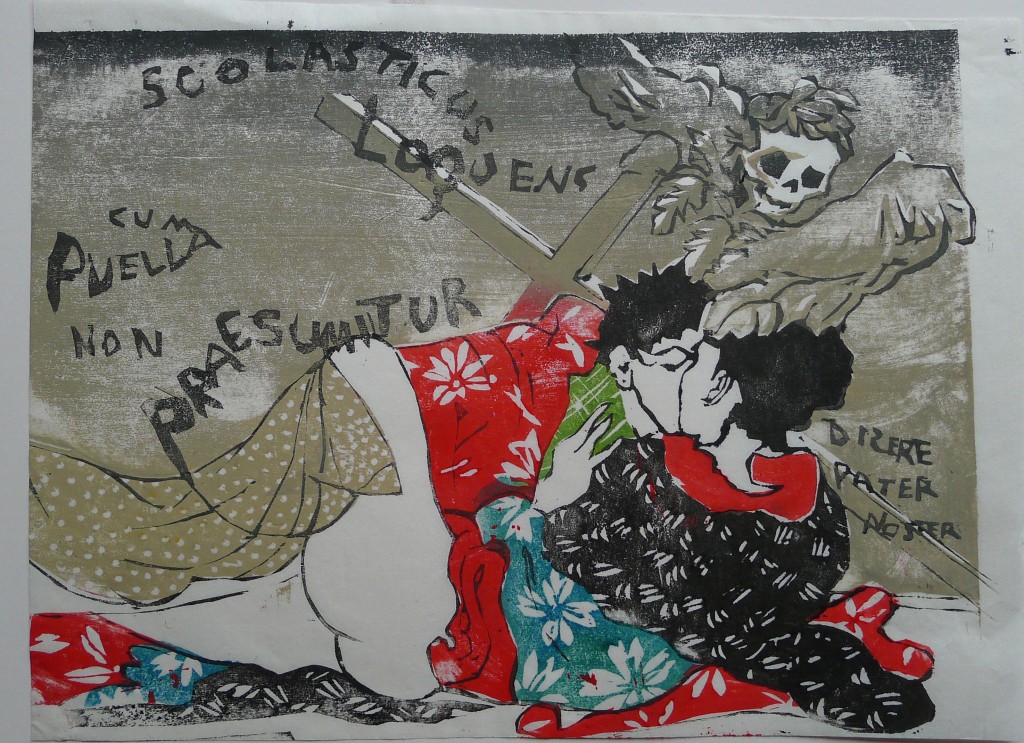

(Exceptionally devoted readers of this blog may recall the expression ‘to strike on nature’s anvil’ – forger sur l’enclume de nature – as the subject of another print and accompanying post).

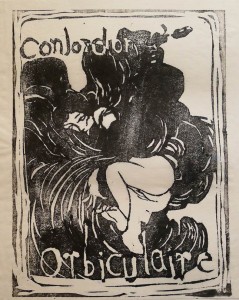

This remarkable big genital thumb without a nail (‘le gros pouce genital despouveu d’ongle’) has inspired one of Dominic Hills’s most recent prints.

The big genital thumb without a nail is clearly so overwhelming that the comedian devotes almost as much attention to it as the number three, although he does eventually return to his purported theme. This was of course only ever a pretext for a whole series of comic conceits like these and indeed an umbilical pistol soon joins this pantheon of phallic imagery (this pistol incidentally requires three things: 1. to be well cocked and full of gunpowder; 2. to be charged with a couple of bullets; 3. to have a new holster, for if you put it in a old rotten holster covered in cobwebs, your pistol will be ruined), making an unholy trinity with the masculine peg (‘cheville masculine’), one of three things needed for procreation…