In early 2013, I was involved in a collaboration with the performance poet and writer Malika Booker, to produce a podcast for the While You Wait series commissioned by Fuel Theatre. The series is an extended meditation on the idea of waiting, and the podcasts can be downloaded and listened to, while you wait for the bus, for a friend, or for the sun to come out. Malika’s podcast is called Waiting … in a Hairdressers, and is a portrait of a Caribbean hairdressers on the Walworth Road in London (close to where I used to live, above a launderette … but that’s another collaborative story). We also made a short film about the podcast, where we talk about the collaborative process and the finished piece. I met Malika to talk about gossip and passing the time, and early modern barbers whose shops became a hive of rumours and tittle-tattle, thanks (according to Erasmus) to the idle men who hung around there. She was particularly interested in anthropological theories of gossip from the 1960s, which see gossip as a kind of grooming activity, one that cements friendships and promotes social cohesion, an idea which plays nicely with the setting she chose for the podcast. Gossiping with your hairdresser might be even better for you than the head massage before the hair cut. Malika’s exploration of a twenty-first century hairdressers reveals a place where people wait, talk, and swop stories, a place you might choose to go and spend time in, even if you weren’t getting your nails done.

Monthly Archives: June 2013

Procne and Philomela: A Cautionary Tale for Babblers

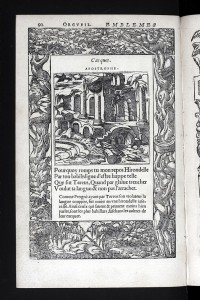

In Andrea Alciato’s famous, influential, and much-translated book of Emblems, can be found this surprising and somewhat troubling appropriation of the Procne and Philomela story.

This is the French translation by Barthélemy Aneau published by Guillaume Rouille and Macé Bonhomme, Lyon, 1549 (the emblem was first published in Latin in 1546):

Pourquoy romps tu mon repos Hirondelle

Par ton babil? digne d’estre huppe telle

Que fut Tereus, Quand par glaive trencher

Voulut ta langue: & non pas l’arracher.Comme Progné ayant par Tereus son violateur la langue couppée, fut muée en une hirondelle jase-resse. Ainsi ceulx qui savent & peuvent moins bien parler, sont les plus babillars, faschans les aultres de leur cacquet.

Why do you disturb my rest, Swallow,

With your babble? Worthy of being a hoopoe

Was Tereus, when with his blade

He sought to sever your tongue: and not to tear it out by the roots.

As Procne, whose tongue was cut out by Tereus her violator, was transformed into a jangling Swallow, so those who know least and talk badly, are the loudest babblers, upsetting others with their cackle.

The emblem shows a solitary bird flying into a ruin, possibly depicting the babbler’s destruction of all civil relationships and communication with her excessive noise. What is odd about the verse and its explanatory gloss is that it almost entirely ignores the violence and abuse in the original Greek myth. In Ovid’s retelling of the story in Metamorphoses, Procne and Philomela were sisters; Procne was married to Tereus, who raped his sister-in-law Philomela, and cut out her tongue so she could not denounce him to her sister. When Philomela managed to tell her story by weaving it into a tapestry she sent to Procne, the two sisters took their revenge by killing Itys, Philomela and Tereus’s son, and serving him up as a meal to his father. Mad with grief, Tereus went after the sisters with a sword but was turned into a hoopoe, while Procne and Philomela became birds: Ovid is not specific, but usually Procne becomes a swallow and Philomela a nightingale. (In the emblem, the names of the sisters are reversed.)

In Alciato’s emblem, this story of rape and extreme vengeance becomes a cry of irritation against a babbler. ‘Procne’ is no longer the victim of horrific violence and the perpetrator of infanticide, but an ignorant woman who doesn’t know when to shut up and so deserves to have her tongue ripped out. The transformation of Tereus from mutilating rapist into a man driven to distraction by a woman’s incessant talk is, to say the least, odd: the horror of the story feels entirely excessive to the point it is used to make. This appropriation of the story as a moralising tale and a warning to babblers, particularly women, suggests that the stereotype of the scolding, gossiping, talkative wife was undercut with an understanding of the relationship between the sexes as one fundamentally based on violence and antagonism. But the remnants of the Greek myth – the parts of the story that aren’t told – are so much in excess of the moral of the emblem that I am left feeling confused and a little disorientated.

Illustrating and Animating Renaissance Nonsense

In an earlier post, I gave some excerpts from a nonsense love poem from 400 years ago that has survived in a manuscript in a library in Paris. Dom Hills has illustrated and animated two of the nonsensical images from this poem, which you can see here:

This 3D concertina print, known as a Polyorama Panoptique, takes us through a key-hole to show us an anvil looking askance at a hammer, as well as a dozen elephants in a plum stone. Such strange and impossible images that are so characteristic of nonsense oblige the reader to do a mental double-take, perfectly illustrated here by a 3D print that also obliges us to shift perspective, steadily revealing new nonsense, much as the poem does.