Reading through Montaigne’s ‘De la gloire’, I came across this piece of verse from Homer’s Odyssey which ventriloquises the Sirens and suggests content for their mysterious enchanting song. On his endless voyage home to Ithaca, Ulysses became the first man ever to resist the singing of the strange, monstrous bird-women, who lured sailors off their ships and dashed them onto the rocks of their island – and so became the first man ever to report the words of the song. Homer and Montaigne after him speculate that the irresistible song is in fact an interpellation, a mirror lifted up to the passing hero that offers him an image of himself that panders to his vanity and is thus spell-binding. Montaigne says:

Le premier enchantement que les Sirenes employent à piper Ulisses, est de cette nature, Deça vers nous, deça, ô tres-louable Ulisse, Et le plus grand honneur dont la Grece fleurisse.

The first enchantment the Syrens employed to deceive Ulisses, is of this nature. ‘Turne to us, to us turne, Ulisse thrice-renowned, / The principall renowne wherewith all Greece is crowned.’

I like this idea that the Sirens offer us visions of ourselves that are irresistible and glorious to us, rather than any other enticement. They seem to play the role of the Lacanian mirror, showing us beyond all doubt that rather than the broken, fragmented, vulnerable creature we feel ourselves to be, we are in fact, whole, competent, capable – heroes, in fact.

I remembered reading a poem by the Canadian novelist Margaret Atwood when I was a teenager about precisely this kind of Siren song which left a lasting impression. Her Sirens also appeal to the hero in the passing sailor – you are my saviour! You will rescue me! – but they use the rhetoric of secrecy as lure in a way that Erasmus would have recognised.

This is the one song everyone

would like to learn: the song

that is irresistible:

[…]

Shall I tell you the secret

and if I do, will you get me

out of this bird suit?

[…]

I will tell the secret to you,

to you, only to you.

Come closer. This song

is a cry for help: Help me!

Only you, only you can,

you are unique

at last. Alas

it is a boring song

but it works every time.

Margaret Atwood, ‘Siren Song’, You Are Happy (1974)

What is clever about Atwood’s poem is that it is only at the end that you realise it is in its entirety the lure, the enchantment: the pose of the damsel in distress, the disillusion with the whole business of shipwrecking sailors. From this point of view it is a real siren song: it is not what it appears to be at first glance: rather than a beautiful singing maiden, it is a hideous squawking beast. But it is only because we want to believe them that they have any power.

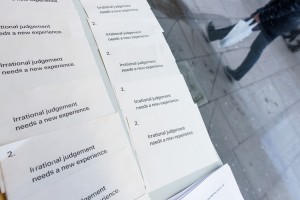

Dom wired his beautiful evocations of Renaissance double entendres into the window and flyposted his ephemeral prints alongside.

Dom wired his beautiful evocations of Renaissance double entendres into the window and flyposted his ephemeral prints alongside. The exhibition took place at the same time as a protest just along the road, where students had occupied the gallery space to contest the sale of the art school.

The exhibition took place at the same time as a protest just along the road, where students had occupied the gallery space to contest the sale of the art school.