In one of several speeches devoted to the joy of cuckoldry and its associated horns, Bruscambille discusses how he put his books to one side and experienced a vision of Europa riding a bull (actually Zeus metamorphosed into a bull to have his way with her) and holding him by the horns while she chants ‘Long live the horn! Long live the horn!’. The comedian goes on to decrypt his vision:

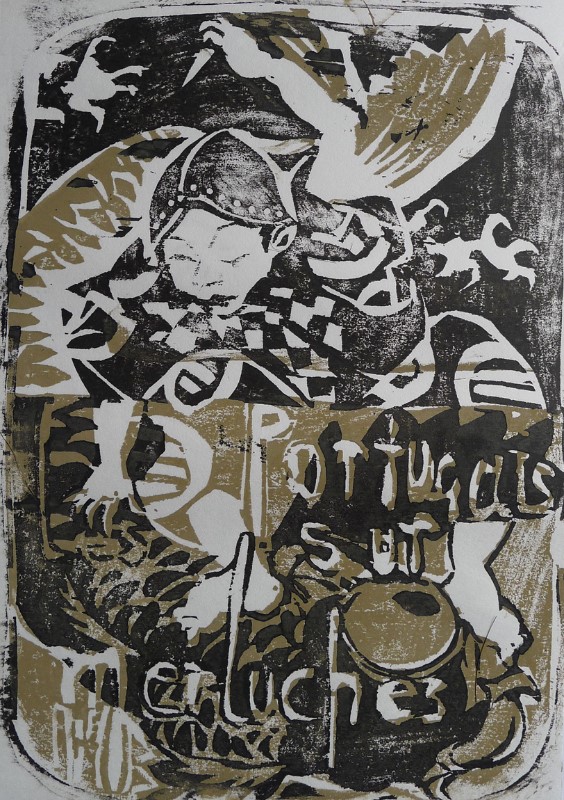

Moy qui mytologise sur une obscurité, comme un Portugais sur les merluches de terre neufve, je m’escrie à gorge desployée Lætandum est.[I who expound on a hidden meaning, like a Portuguese man on the pollocks of Newfoundland, I cry out to the top of my lungs, Lætandum est [Let’s rejoice!]]

There were plenty of fish in the seas around Newfoundland, their bounty was practically proverbial. Bruscambille’s allusion to a Portuguese fisherman talking about pollocks from that part of the world would then doubtless have made sense to his audience. Similarly, in another speech that is virtually nonsensical, Bruscambille opens by telling his audience that he has brought them cod from Newfoundland, but for us this is the piece of cod that passes all human understanding.

The man from Portugal and his pollocks had not fully registered with me until a trip to Paris to give a talk about nonsense and humour. One of the colleagues there, a recent PhD graduate from the Sorbonne, Dr Tiphaine Rolland, knew this passage off by heart. She had indeed recited it at her doctoral thesis defence – a much more public affair than in Britain – concluding her opening statement with it, before being interrogated by the assembled jury of professors about her thesis on the origins of La Fontaine’s fables and tales in sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century comic works like those Bruscambille.

Even if the Newfoundland seas are sadly no longer so full of fish, the ripples of their erstwhile abundance are still being felt, returning to Paris and then making their way to Devon, where they have inspired Dominic Hills’s latest print, ‘Portugais sur merluches’ [A Portuguese man on pollocks]

How Hills came by this visual version of Bruscambille’s speech is something of a mystery in itself. Some say after a week spent drinking absinthe he was so exhausted he fell asleep in his garret and a vision of a man battling a giant fish with nonsensical French settled on his consciousness like a phantom from another world. This is what happens when four-hundred-year-old pollocks swim mentally from Newfoundland to Paris to south-west England, which, in some ways, is where it all began, over the border, in Cornwall, for Bruscambille’s speech is called ‘En faveur des privileges de Cornuaille’ [In favour of the privileges of Cornwall], because ‘Cornuaille’ in French suggests ‘corne’ or ‘horn’ and, hence, ‘the forked, or cornuted, order’, as Randle Cotgrave translates it. So the cuckolds’ horns of plenty are indeed endlessly fertile and have come full circle. In other words, it’s all a load of pollocks.