Sometime after 1588, 8 years after he published the first edition of the Essais, Michel de Montaigne added this Latin epigraph to his ever-growing, ever-increasing book: Viresque adquirit eundo, ‘winning vigour as she goes’. The quotation is from Virgil’s Aeneid, and describes the goddess Rumour, flying through Libya on swift and eager wings to broadcast the news of Aeneas and Dido’s dalliance, their amorous and voluptuous winter. ‘Rumour!’ exclaims Virgil. ‘What evil can surpass her speed?’

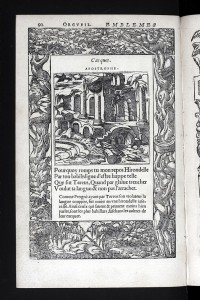

Here she is in a sixteenth-century woodcut by Hans Weigel, with rustling wings and eyes all over her body:

Virgil’s Fama

Montaigne tackles the issue of rumour himself in a chapter from Book 3, ‘Des boyteux’ (‘Of the Lame’). Here he talks of the plentiful ‘miracles’ – monstrous births, falling stars, plagues, and other portents – that had been spawned by the anxieties and suspicions of civil-war-torn France. His ‘miracles’ are very much products of the human imagination, however: they are born and gain persuasive power through our innate desire to exaggerate and amplify; to embroider a good story. This is how he describes the work of Rumour:

J’ay veu la naissance de plusieurs miracles de mon temps. Nous faisons naturellement conscience de rendre ce qu’on nous a presté sans quelque usure et accession de nostre creu. L’erreur particuliere faict premierement l’erreur publique, et à son tour apres, l’erreur publique faict l’erreur particuliere. Ainsi va tout ce bastiment, s’estoffant et formant de main en main: de maniere que le plus esloigné tesmoin en est mieux instruict que le plus voisin, et le dernier informé mieux persuadé que le premier. C’est un progrez naturel.

In John Florio’s magnificent 1603 translation:

I have seen the birth of divers miracles in my dayes. We naturally make it a matter of conscience, to restore what hath beene lent us, without some usury and accession of our increase. A particular errour, doeth first breede a publike errour: And when his turne commeth, a publike errour begetteth a particular errour. So goeth all this vast frame, from hand to hand, confounding and composing it selfe; in such sort that the furthest-abiding testimonie, is better instructed of it, then the nearest: and the last informed, better perswaded then the first. It is a natural progresse.

The ‘natural progress’ of rumour means that the miracle itself is inflated, blown out of all proportion and even all recognition, as the story is passed along the line, gaining substance as it goes. The whole process sounds like a particularly frantic and creative game of Chinese Whispers, where each teller is more convinced of the truth of the story than the last. As it is passed along, moving in and out of the public domain, error becomes contagious and infects all who come into contact with it. What makes rumour particularly pernicious is the subjective investment people seem unable to resist making in the story that they are passing on: it becomes almost a moral duty, a matter of ‘conscience’, to make the rumour more credible with some little added detail, or some clinching convincing witness.

So, Montaigne goes on to say, once we have risked our own credibility on a particular rumour, we are disproportionately attached to its future success; rejecting a rumour means rejecting the credibility of all those who have believed it. Irrational and arbitrary attachment to a story means that any resistance it encounters is met by the violence of frustrated opinion. Montaigne lists in a crescendo some increasingly violent responses: ‘le commandement, la force, le fer, et le feu’, ‘commandment, force, sword, and fire’. Since this chapter is, amongst other things, a plea for moderation and clemency in witchcraft trials, the fire that ends the list brings to mind the pyres on which heretics and witches were burned alive throughout sixteenth-century Europe; an association that Montaigne makes himself in a celebrated aphorism that comes a little later in the chapter: ‘Après tout, c’est mettre ses conjectures à bien haut pris que d’en faire cuire un home tout vif’ (‘When all is done, it is an over-valuing of ones conjectures, by them to cause a man to be burned alive’).