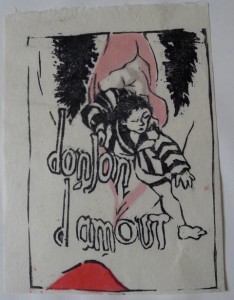

Here is Dominic Hills’s video animation of his print of an old French saying about a big bottom, ‘a household arse, food and drink supplied’ (‘un cul de ménage, il y a à boire et à manger’):

Those with good French will notice some deliberate mistakes in the spelling, to mimic the printers’ errors that are so frequent in early printed books and that annoyed authors, who would complain about their printers in prefaces typset by those same printers.

One such author was Bruscambille (see previous posts) who, at the end of his speech in praise of the pleasure of defecation (‘En faveur de la félicité chiatique’) comments that ‘escornifleurs’, that is to say, in Cotgrave’s translation, ‘A base pickthanke, or parasite; greedie feeder, or smell-feast; one that carries tales, jeasts, or newes from house to house, thereby to get victualls’, or, in the deflatingly prosaic modern vernacular, a ‘freeloader’, will always find in the loos of great houses ‘some household arse, who will save them something to eat and drink’ (‘quelque Cul de mesnage, qui leur conservera à boire et à manger’).

Bruscambille’s audience would have recognized this expression. As if to demonstrate how widespread it was, modern dictionaries note that the heir to the throne, the not quite three-year-old future Louis XIII, was introduced to it in August 1604. In his journal, Louis’s doctor, Jean Héroard, notes the following exchange between the young prince and one of the courtiers:

“Monsieur, voilà Mama dondon qui a un cul de mesnage où il y a à boire et à manger”. Respond: “Et moy aussy”. “Par où boit-on?” Resp.: “Par là”, monstrant sa guillery. “Par où mange-t-on?’ Resp.: “Pa là”, monstrant de la main son derriere en sousriant. (ed. Foisil, I, 504).

[“Sir, there’s Mama fatty with her household arse, food and drink supplied”. Replies: “Me too”. “Where does one drink from?”. Reply: “From there”, pointing to his willy. “Where does one eat from?”. Reply: “From there”, gesturing towards his bottom and smiling.]

Cotgrave translates ‘dondon’ as ‘A short, fat, and grosse woman; a femall bundle of farts’. Indeed, the household arse is not to be confused with the household fart (‘pet de ménage’), which is found in Rabelais among others, although the household fart also comes with food and drink supplied…

Dominic Hills takes inspiration from old French naughtiness, Japanese print-making and revolutionary art from the May ’68 student rebellion in Paris. Japanese print-making also catered for working-class culture, including advertising, while the May ’68 revolutionary posters produced by art students turned Paris into a gallery for strange and rebellious images.

Dominic Hills takes inspiration from old French naughtiness, Japanese print-making and revolutionary art from the May ’68 student rebellion in Paris. Japanese print-making also catered for working-class culture, including advertising, while the May ’68 revolutionary posters produced by art students turned Paris into a gallery for strange and rebellious images.

In 1647, the grammarian and prime mover in the emasculation of the French language, Claude Favre de Vaugelas, remarked in his Remarks on the French Language of his pride in knowing a man who never pronounced the word ‘thing’ (‘chose’) because it was a word with which people make dirty jokes.

In 1647, the grammarian and prime mover in the emasculation of the French language, Claude Favre de Vaugelas, remarked in his Remarks on the French Language of his pride in knowing a man who never pronounced the word ‘thing’ (‘chose’) because it was a word with which people make dirty jokes.![Jeu du bilboquet [print] Jeu du bilboquet [print]](http://gossipandnonsense.exeter.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/jeu_du_bilboquet-218x300.jpg)