Throughout the Gossip and Nonsense project Emily and I have been using Sol LeWitt’s sentences on conceptual art as phrases to ‘chinese whisper’. Written in 1969 these were first published in the magazine 0-9 in New York, and in Art-Language in London (both 1969). I’ve gradually been setting the resulting ‘translated’ sentences using metal letterpress type.

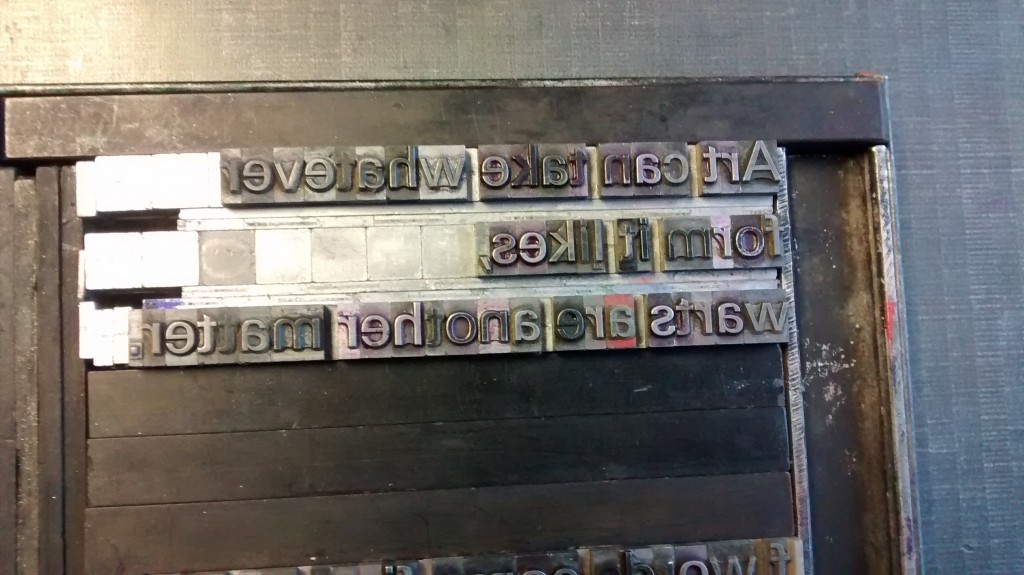

Possibly the most laborious way to produce a printed page, letterpress appeals to me because of the amount of care that it requires; the decision making and accuracy; and the physicality of the heavy-weight cubes of metal; the sound of the sticky ink; the smell of news print; and the effort required to pull the press.

To date (August 2015) the following sentences have been whispered and printed in an edition of 30, on newsprint.

1. Conceptual art are eternal optimists.

(whispered by London Met staff Cat Jeffcock, Aimee McWilliams, Charlotte Worthington and Marianne Forest in English)

12. For each work of art that comes from a circle there are many variations

(whispered by artists group members: Rebecca French, Agnieszka Gratza, Karen Christopher, Sheila Ghelani, Clare Qualmann in English)

14. The words of one artist to another might induce an idea strain.

(whispered by artists group members: Rebecca French, Agnieszka Gratza, Karen Christopher, Sheila Ghelani, Clare Qualmann in English)

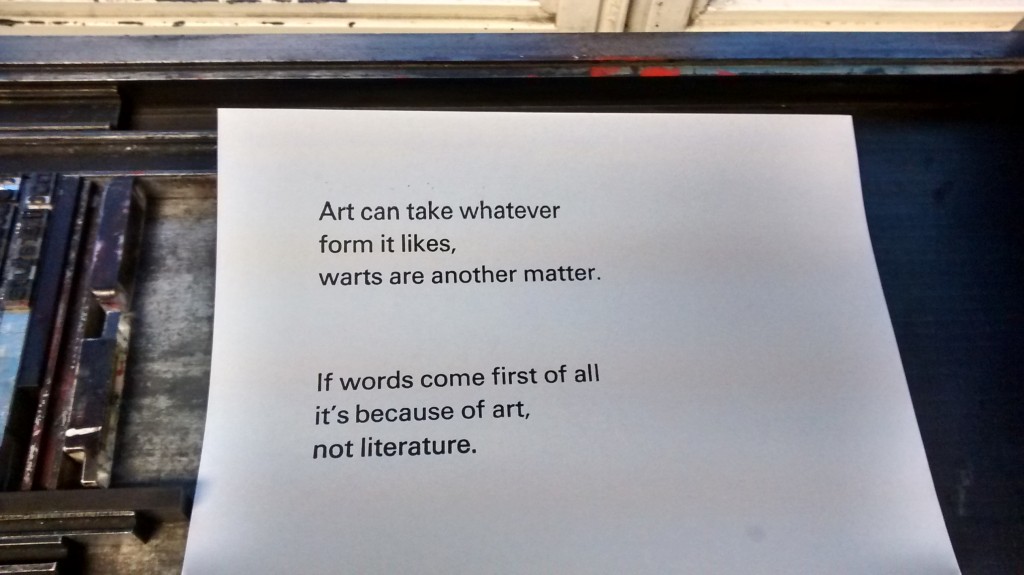

15. Art can take whatever form it likes, warts are another matter

(whispered by participants in the Gossip and Nonsense symposium, Exeter, June 2013, in English and French)

16. If words come first of all it’s because of art, not literature.

(whispered by participants in the Gossip and Nonsense symposium, Exeter, June 2013, in English and French)

20. Successful art challenges our perceptions by changing our understanding.

(whispered by participants in the Renaissance Rumours event at Inside Out, King’s, October 2014, in English and French)

26. The artist makes the seed, but others do their own.

(whispered by London Met Fine Art students, May 2015, in English)

27. The concept of a work of art may involve the people.

(whispered by artists group members: Rebecca French, Agnieszka Gratza, Karen Christopher, Sheila Ghelani, Clare Qualmann in English)

34. When an artist makes his scene he makes his scene well.

(whispered by London Met Fine Art students, May 2015, in English)

You can compare the original sentences here.