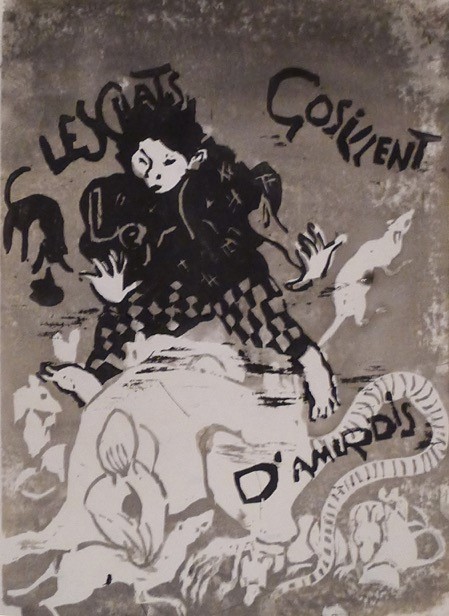

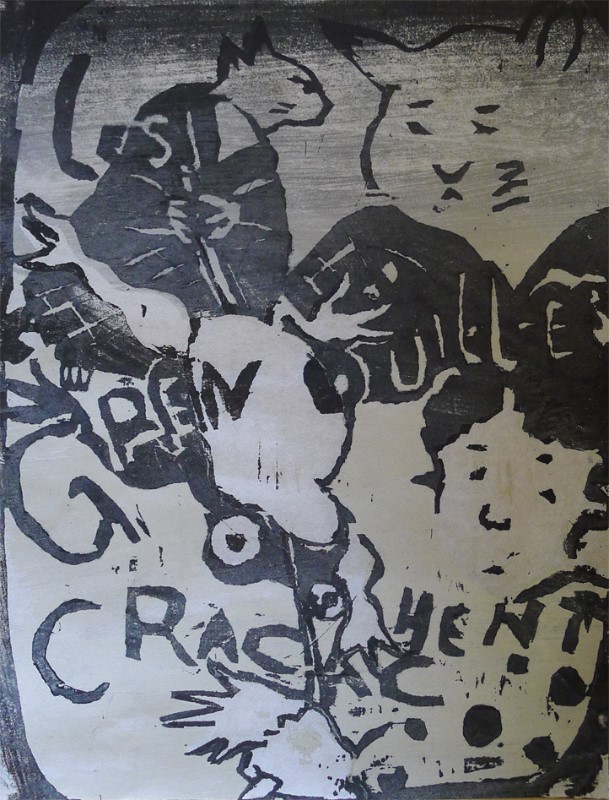

Dominic Hills has produced the latest in a series of images inspired by the opening of one of Bruscambille’s nonsense speeches. Following his prints of pregnant women pissing their maidenhead and dogs shitting tar as well as frogs spitting out cooked goslings, now we have cats guzzling a confection of turds (‘les chats gosillent le diamerdis’). This ‘diamerdis’ – a confection of turds or pilgrim’s salve, both translations from Randle Cotgrave’s essential Dictionarie of the French and English Tongues of 1611 – alludes to the very real practice of using faecal matter in contemporary medical treatments. Indeed, in Rabelais’s Pantagruel, Panurge sews Epistemon’s head back on with the aid of diamerdis powder, which he always has about his person, and which helps cure Epistemon of his beheading. In Bruscambille, the ‘chats’ continue the tongue-twister of ‘les chiens chient’. In any case, it is scarcely surprising that some of the animals in Dominic Hills’s image seem decidedly unwell.

Author Archives: Hugh Roberts

Curioser and curioser

In a 1640 dictionary of linguistic curiosities, the royal interpreter Antoine Oudin gives definitions of a number of peculiar expressions for the benefit of foreigners seeking to master French, including the following (marked with an asterisk to denote that it should be handled with care):

* en Papagosse où les chiens chient la poix. i. en un lieu inconnu. vulg.

[* in Papeligosse where dogs shit tar, i.e. in an unknown place. vulgar]

The imaginary land of Papagosse, aka Papeligosse, is rendered in Randle Cotgrave’s 1611 Dictionary of the French and English Tongues as ‘the country of the butterflies’. Oudin’s definition is undoubtedly right, since this place is indeed unknown, but it rather misses the joke.

In fact, this curiosity comes from a nonsense speech we have already encountered by the comedian known as Bruscambille, which also features frogs spitting out cooked and stuffed geese and pregnant women doing impossible things.

In addition to being a piece of nonsense, the phrase contains a miniature tongue-twister ‘les chiens chient’ (similarly, in another speech, Bruscambille says he has been sent off to ‘chasser les vaches aux champs’ [literally, to hunt cows in the fields]) – doubtless obvious to the original audience, these elocutionary acrobatics become blink-and-you-miss-it on the printed page.

Antoine Oudin had Bruscambille’s speeches on his desk when compiling his dictionary – quite what his putative readership made of such expressions, or whether any non-French speaker dropped them into conversation down the tavern in mid-seventeenth-century Paris to impress the locals, has been lost in the mists of time.

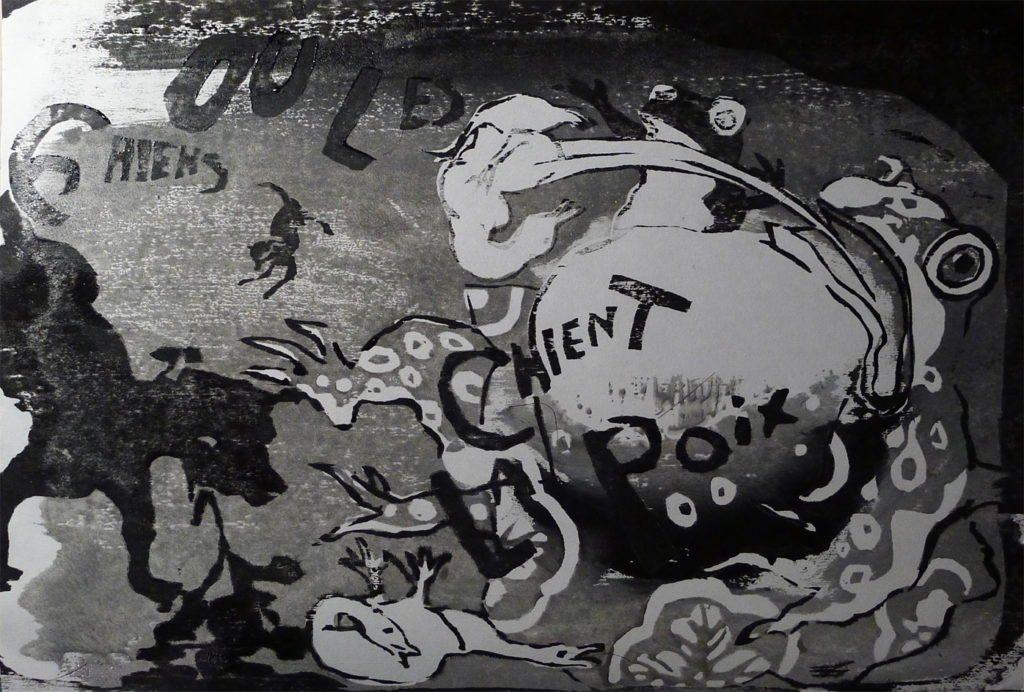

The fact that Oudin picked up this supposed saying shows how Bruscambille’s speeches in general, and his nonsense in particular, provided rich pickings for anyone interested in unusual phrases. From this perspective, nonsense is a kind of linguistic laboratory for producing arresting imagery and expressions, which in turn may explain why Dominic Hills has returned to the brief extract from which this phrase is taken for his latest print ‘où les chiens chient la poix’ [where dogs shit tar]:

Obscenity and nonsense

In a nonsense speech from the early seventeenth century, the comedian known as Bruscambille reports how pigs dressed in the Turkish fashion launch a naval battle on the sail of a windmill in the lands of Papeligosse, where dogs shit tar, cats guzzle a confection of turds, pregnant women piss a maidenhead as big as an arm and frogs spit out fully cooked and stuffed geese.

The frogs have already made an appearance in one of Dominic Hills’s prints, and this same nonsensical passage has inspired two others, both based on the obscene impossibility of pregnant women pissing a maidenhead as big as an arm [les femmes enceintes pissent un pucelage gros comme le bras] (incidentally, the word ‘bras’ [arm] has disappeared behind one of the frogs who has flown into the frame).

Nonsense writers are fond of impossibilities like this. Bruscambille’s imagery is as strikingly grotesque as what it describes is unlikely. Nonsense may be gibberish that suggests an abstract meaning which can never be reached. In this passage, the opposite applies: the scatalogical imagery conjures up pictures that have an imaginative potency, the impossible made tangible. Hence obscenity and nonsense are often yoked together, making the unreal real, which in turn gives a hint as to why such writing is suggestive to a contemporary visual artist.

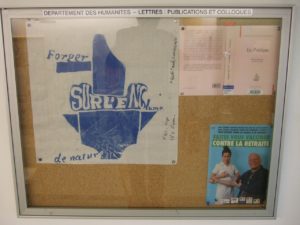

The Spirit of ’68

I was in Paris in May 2018, 50 years too late to witness the famous student protests and general strike that ensued. Under the pretext of giving a talk on nonsense at the Sorbonne, the visit was nevertheless a chance to pay homage to that rebellious spirit. The brilliant and highly influential posters produced by art students during the 1968 riots had already inspired Dominic Hills’s imagery, especially ‘Forger sur l’enclume de nature‘ (to forge on nature’s anvil), which takes it cue from a poster showing the worker’s hammer striking down on ‘Capital’.

It seemed only proper then that I should take hold of the means of production and distribution, so I learned how to make a print from the block designed and cut by Dominic Hills, to take some copies with me to Paris:

My hopes of fly-posting some copies at Parisian universities were scuppered by the security triggered by there being a very real re-enactment of May ’68 going on, as students and other workers were protesting against government reforms of higher education, among other things.

Fortunately, however, my colleague and fellow nonsense expert, Dr Jean-Marc Civardi, was happy to take a copy and display it at his university, where, as far as I know, it remains. Hence not only the image, but also the slogan have returned to their place of origin – ‘to forge on nature’s anvil’ a reminder of old ribaldry and the fact that May ’68 was also a far-reaching sexual revolution. The impact of this visual hammer blow boomeranging back to Paris remains to be seen.

Spitting frogs

In 1939, a group of surrealists produced a collaborative novel, including several stories by the English artist Leonora Carrington. One of these, ‘The Skeleton’s Holiday’, becomes particularly nonsensical:

It happened that one day the skeleton drew some hazelnuts that walked about on little legs across mountains, that spit frogs out of mouth, eye, ear, nose and other openings and holes…

This reminded me of some early seventeenth-century French nonsense by the comedian known as Bruscambille, which discusses frogs dressed in the Turkish fashion, fighting a naval battle on the wing of a windmill, in the land of the fairies where, among other things, cats guzzle a confection of turds and frogs spit roasted and stuffed goslings (etc.)

Academically, such anachronism is a crime: nonsense writers from the distant past could not have been surreal so long before the surrealist movement was formed in the 1920s. But nonsense is much older than surrealism so Carrington, knowingly or not, is drawing on images and techniques that reach back well before Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear. Nonsense predicts surrealism.

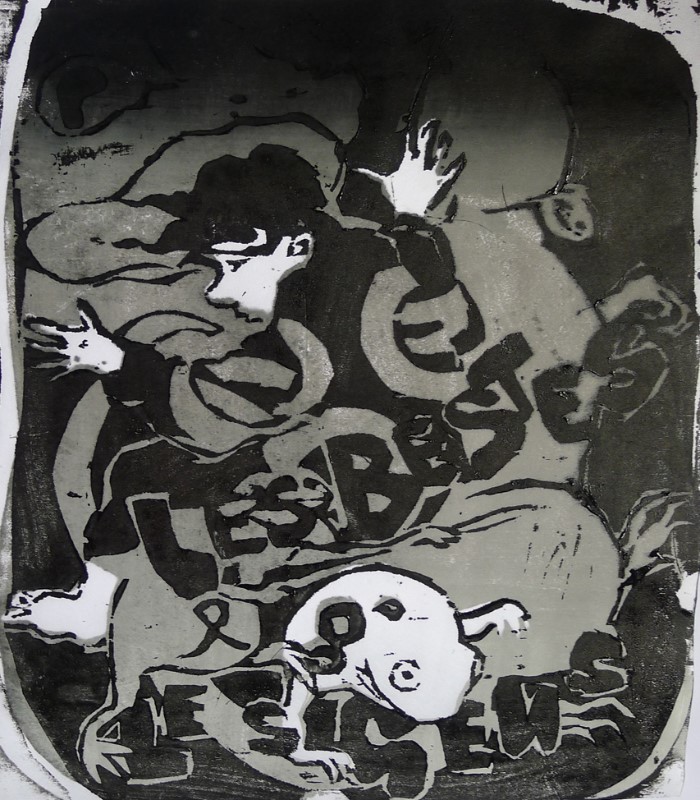

Bruscambille’s imagery, especially the cats and frogs, has inspired Dominic Hills’s latest print, given a further twist as the poor frog, rather than spitting roasted goslings, becomes spit-roasted, a lapsus lectionis, or slip of reading, of which Freud and the surrealists would themselves have approved:

Les bestes et les gens/Beasts and people

Dominic Hills’s latest print, ‘Les bestes et les gens’ (‘Beasts and people’), presents a disconcerting vision of an individual enveloped by rats and frogs. To my eyes, this image, inspired in part by Utagawa Kuniyoshi, is also reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch or Arcimboldo or even of Sartre’s descriptions of nausea.

The verbal prompt for the print comes from a piece of nonsense by Bruscambille, in which the comedian takes his cue from Rabelais. The master had slipped a blink-and-you-miss-it insult into an episode of gibberish – ‘Quand le soleil est couché toutes bestes sont à l’ombre’ (‘When the sun is wholly set, all beasts are in the shade’) – which the apprentice incorporates into one of his speeches, to toy with his audience:

L’autre soir comme le Soleil estoit couché, toutes les bestes, Messieurs, estoient à l’ombre, comme vous estes, je rencontray un grand petit homme rousseau, qui avoit la barbe noire, lequel venoit d’un pays, où excepté les bestes & les gens, il n’y avoit personne

[The other evening as the sun had set, all beasts, gentlemen, were in the shade, as you are, I met a tall short man with red hair, who had a black beard, and who came from a country where, except beasts and people, there was no-one]

The insult is more obvious in Bruscambille’s version but still the audience would have had had to keep up with him so, deliberately and perversely, only the clever ones would have got it that he was saying they were idiots. Equally, a moment’s thought tells us that a country where, except animals and people, there is no-one, is any country you might care to visit. Unless, that is, you push the meaning of ‘no-one’ and end up in the dystopian world depicted by Dominic Hills’s subtle knife.

Fisherman’s tales

In one of several speeches devoted to the joy of cuckoldry and its associated horns, Bruscambille discusses how he put his books to one side and experienced a vision of Europa riding a bull (actually Zeus metamorphosed into a bull to have his way with her) and holding him by the horns while she chants ‘Long live the horn! Long live the horn!’. The comedian goes on to decrypt his vision:

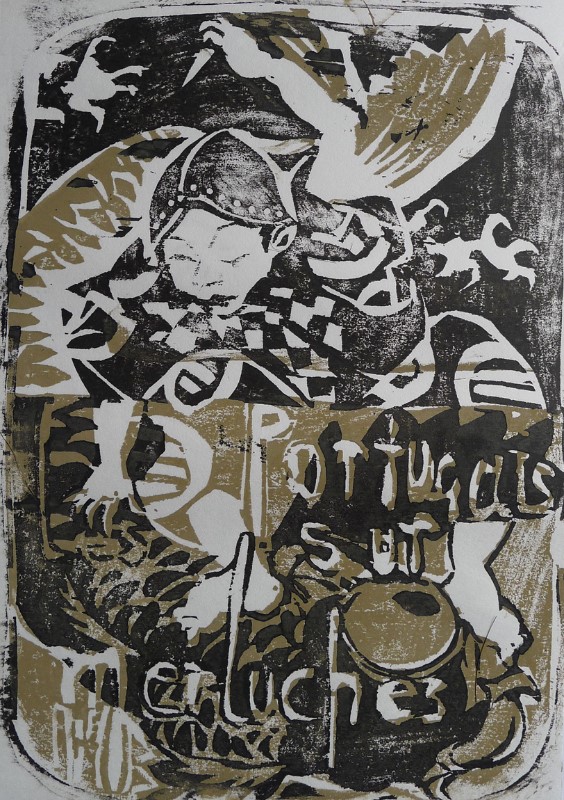

Moy qui mytologise sur une obscurité, comme un Portugais sur les merluches de terre neufve, je m’escrie à gorge desployée Lætandum est.[I who expound on a hidden meaning, like a Portuguese man on the pollocks of Newfoundland, I cry out to the top of my lungs, Lætandum est [Let’s rejoice!]]

There were plenty of fish in the seas around Newfoundland, their bounty was practically proverbial. Bruscambille’s allusion to a Portuguese fisherman talking about pollocks from that part of the world would then doubtless have made sense to his audience. Similarly, in another speech that is virtually nonsensical, Bruscambille opens by telling his audience that he has brought them cod from Newfoundland, but for us this is the piece of cod that passes all human understanding.

The man from Portugal and his pollocks had not fully registered with me until a trip to Paris to give a talk about nonsense and humour. One of the colleagues there, a recent PhD graduate from the Sorbonne, Dr Tiphaine Rolland, knew this passage off by heart. She had indeed recited it at her doctoral thesis defence – a much more public affair than in Britain – concluding her opening statement with it, before being interrogated by the assembled jury of professors about her thesis on the origins of La Fontaine’s fables and tales in sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century comic works like those Bruscambille.

Even if the Newfoundland seas are sadly no longer so full of fish, the ripples of their erstwhile abundance are still being felt, returning to Paris and then making their way to Devon, where they have inspired Dominic Hills’s latest print, ‘Portugais sur merluches’ [A Portuguese man on pollocks]

How Hills came by this visual version of Bruscambille’s speech is something of a mystery in itself. Some say after a week spent drinking absinthe he was so exhausted he fell asleep in his garret and a vision of a man battling a giant fish with nonsensical French settled on his consciousness like a phantom from another world. This is what happens when four-hundred-year-old pollocks swim mentally from Newfoundland to Paris to south-west England, which, in some ways, is where it all began, over the border, in Cornwall, for Bruscambille’s speech is called ‘En faveur des privileges de Cornuaille’ [In favour of the privileges of Cornwall], because ‘Cornuaille’ in French suggests ‘corne’ or ‘horn’ and, hence, ‘the forked, or cornuted, order’, as Randle Cotgrave translates it. So the cuckolds’ horns of plenty are indeed endlessly fertile and have come full circle. In other words, it’s all a load of pollocks.

When the sun is wholly set all beasts are in the shade

In the nonsensical court case between the lords Baisecul and Humevesne (Kissebreech and Suckfist), in Rabelais’s Pantagruel (1532) the latter makes the following statement in the wonderfully evocative translation by Sir Thomas Urquhart:

If any poor creature go to the stoves to illuminate his muzzle with a cowsherd or to buy winter-boots, and that the sergeants passing by, or those of the watch, happen to receive the decoction of a clyster or the fecal matter of a close-stool upon their rustling-wrangling-clutter-keeping masterships, should any because of that make bold to clip the shillings and testers and fry the wooden dishes? Sometimes, when we think one thing, God does another; and when the sun is wholly set all beasts are in the shade. Let me never be believed again, if I do not gallantly prove it by several people who have seen the light of the day.

The emboldened phrase is one of several plays on words, which is clearer in the original French:

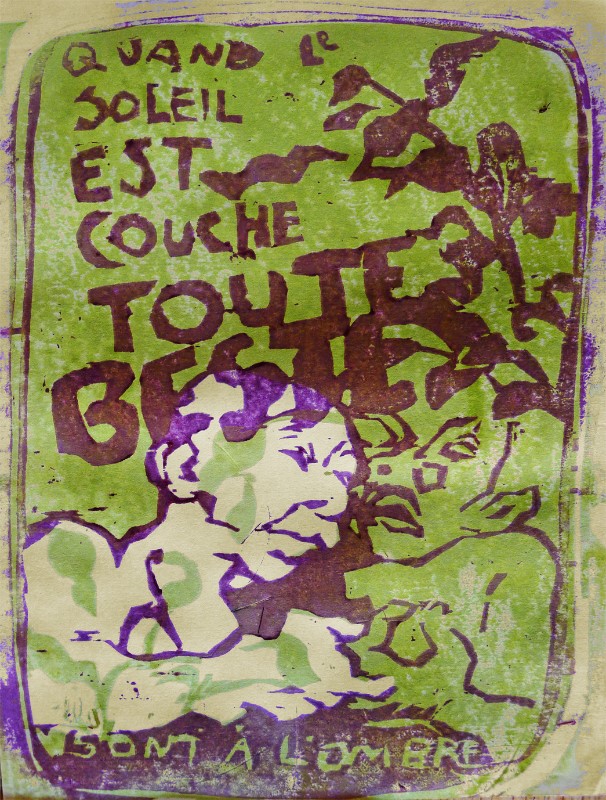

Quand le soleil est couché, toutes bestes sont à l’ombre

It’s a joke on the ambiguity of beste, which means either beast or idiot (or, better, one of Randle Cotgrave’s translations, including sot, doult, loobie, blockhead). In other words, it’s a blink-and-you-miss-it insult hidden within the gibberish. It implies of course that we are all loobies and, incidentally, that the Lord of Suckfist will struggle to find ‘people who have seen the light of the day’ – we as readers are in the dark about what he and the Lord of Kissebreech are debating so animatedly yet ludicrously.

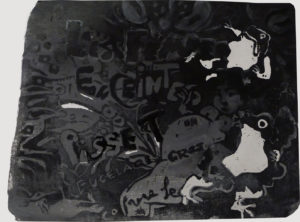

I mentioned this expression to Dominic Hills recently, as I was about to discuss it at a research seminar at the Sorbonne. He rapidly produced a print inspired by the beasts/idiots, which happily I was able to project during my talk:

Subsequently it emerged that the shaded monsters/loobies are inspired by Goya, the whole effect by Ver sacrum, the green and purple shades by a plant, and so forth, a whole soup of influences of which Rabelais would have approved.

Working on such research, talking nonsense at the Sorbonne means being in the shade, of course. Dominic Hills’s print reminds us of Rabelais’s original creativity, not to mention nonsense, and thereby helps take us back into the light of day.

Playing on nature’s flute and the mute bagpipe

Implausibly devoted readers of this blog may remember that the early seventeenth-century French comedian known as Bruscambille has a speech on castrati (controversial figures, believed to be ideal lovers, since some allegedly could maintain an erection but obviously without any risk of pregnancy, hence they became the target an entirely serious injunction issued by the high court of Paris, which was concerned that eunuchs might corrupt women…) in which he makes the following observation about Spring:

In this pleasing season, the pilgrim starts planting his staff while the shepherd starts playing on nature’s flute and the mute bagpipe in the shade of the shepherdess’s mossy mound. In short, at this time, everything lives, everything dances, and breathes only orbicular conjunction.

[En ceste agreeable saison, le Pelerin commence à planter son bourdon, le berger à jouer du flageollet de nature, et de la cornemuse sourde à l’ombre du tertre moussu de la bergere. Bref, en ce temps tout vit, tout dance, et ne respire que la conjunction orbiculaire.]

He goes on to comment how sad it is that castrati cannot ‘chime and ring their bells’ to celebrate the arrival of sweet Spring.

Dominic Hills already turned the ludicrously Latinate phrase ‘conjunction orbiculaire [orbicular conjunction]’ into one of his woodcuts and now he returns to this same speech for the source of his latest version of Japanese erotic prints (shunga), ‘jouer du flageollet de nature, et de la cornemuse sourde’ [to play on nature’s flute and on the mute bagpipe]

Bruscambille’s image reminds me of Peter Cook’s famous satire of the judge’s summing-up in the Jeremy Thorpe trial of 1979 in which he describes a thinly-veiled version of the male model Thorpe was charged with conspiring to have killed as ‘a scrounger, a parasite, a pervert, a worm, a self-confessed player of the pink oboe‘. Cook wrote the speech the night of its performance, surrounded by other great comedians. As Harry Thompson notes in his biography of Cook, Michael Palin recalls that two minutes before going on stage, he was seeking out a euphemism for homosexual and Billy Connolly ‘with the air of a scholar recalling some medieval Latin’ remembered hearing someone described as a ‘player of the pink oboe’. Two minutes later, the brilliant Cook was on stage, throwing in ‘self-confessed’ for good measure.

Nature’s flute and the mute bagpipe do not have the political force of Cook’s player of the pink oboe, even if Bruscambille’s speech does satirize what now appear to be unlikely anxieties about eunuchs. Nevertheless, it is still pleasing to think of a kind of comic continuum between performers and audiences over the centuries, delighting in this kind of humour and indeed preserving and transmitting it (viz. Michael Palin saying that Billy Connolly was like a ‘scholar recalling some medieval Latin’), which this blog has also sought to do.

Drive the peg in

In his speech in praise of a nymph’s tits (‘En faveur des tetins d’une nymphe’), the early seventeenth-century French comedian known as Bruscambille describes an apparently disturbing dream involving this part of the female anatomy. He is saved from this nocturnal vision by seeing a Latin saying at the end of Mercury’s wand: ‘Quae mutuo sumpseris pari vel etiam | Maiori mensura reddas’ [‘Take fair measure from your neighbour and pay him back fairly with the same measure, or better, if you can’] (Hesiod, Works and Days, 349-51).

Disarmingly claiming to understand Latin like a cow, he gives his own version of Hesiod’s moral injunction:

Pour mettre la femme a son aise,

Il la convient un peu flatter,

Mais pour du tout la contenter

Il faut cheviller la mortaise.

My Exeter colleague and translator of Guillaume Apollinaire and many others, Professor Martin Sorrell, has rendered this little poem as follows:

To make a woman drop her guard,

Flatter her somewhat.

But to please her, find the slot

And drive the peg in hard.

Clearly, Bruscambille has an unusual take on the dictum about paying your neighbour back the same, or better, but what, one may well ask, has all this to do with tits? The answer lies in the fact that men pay women back for their bosomy apples with their Priapic pears, which are accompanied by comforting and stiff branches.

This noble image of human cooperation and exchange has inspired one of Dominic Hills’s most recent prints, itself inspired, as ever, by Japanese erotic prints known as shunga. And of course this whole blog is the result of an exchange of the fruits of academic research and artistic practice. Thus Hesiod’s view from the seventh or eighth century B.C. resonates centuries later, in the early 1600s in France, through to the present internet age, as humans continually exchange their apples and pears, whether to ‘drive the peg in’ (‘cheviller la mortaise’), or for other pursuits.

P.S. Men also drive the peg in to hang four hams from it, but that is another story.

Cheviller la mortaise

© Dominic Hills