In his speech on cuckolds and the usefulness of horns, the French comedian known as Bruscambille (see previous posts) observes that cuckolds embody generosity and are showered with honours by those who visit them and especially their wives.

He continues to justify his view of the happy lot of the cuckold by referring to a proverb:

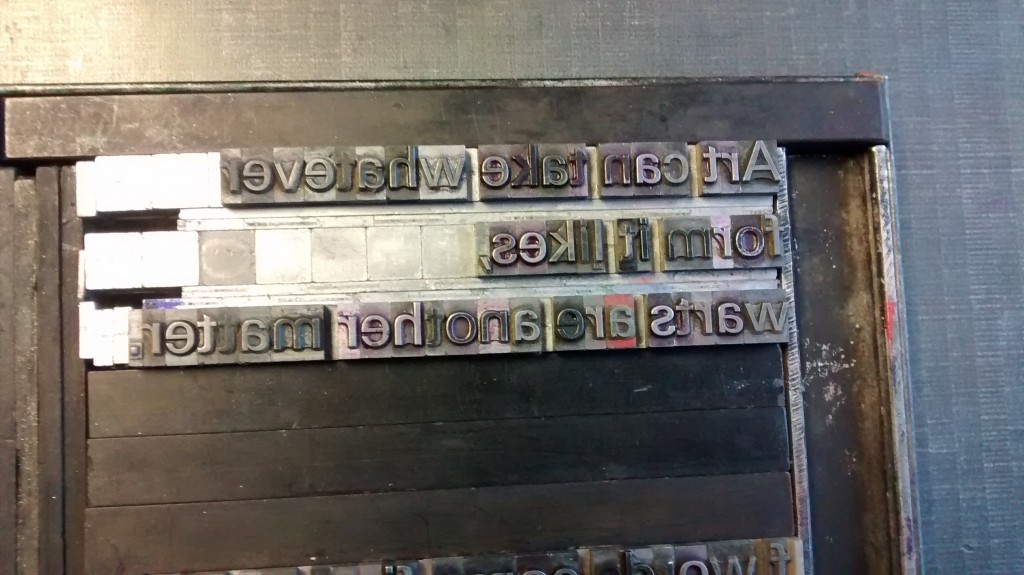

I only need the common proverb to justify my statement, that all men are cousins to whoever has a beautiful wife: how much doffing of caps, how many recommendations and humblings, hugs and bows: for the gifts of fortune, the horn of Amalthea never overflowed like that of a man of good judgement who knows how to manage his household affairs, his horns produce for him, it’s a dairy cow that never runs dry, a meadow that always makes hay, that he can cut a hundred times a day, it’s a mine that he has at home, the more you dig it, the less you empty it, a garden that brings forth new flowers every day, what more shall I say? an infinite seed plot, an inestimable treasure.

[Je ne veux que le proverbe commun pour verifier mon dire, que quiconque a belle femme tout le monde est son cousin, combien aura-il tous les jours de coups de chapeau, de recommendations & submissions, de caresses & de reverences : pour les biens de fortune, jamais la corne d’Amalthée n’en repandit tant que celle d’un homme de bon jugement & qui sçayt bien mesnager, les siennes luy en produisent, c’est une vache à laict qui ne tarit point, c’est un pré de perpetuelle fenaison, qu’il peut tondre cent fois le jour, c’est une miniere qu’il tient en sa maison, que plus on fouit & moins on vuide, c’est un jardin qui chaque jour esclost de nouvelles fleurs, que diray-je plus ? une pepiniere infinie, un thresor inestimable.]

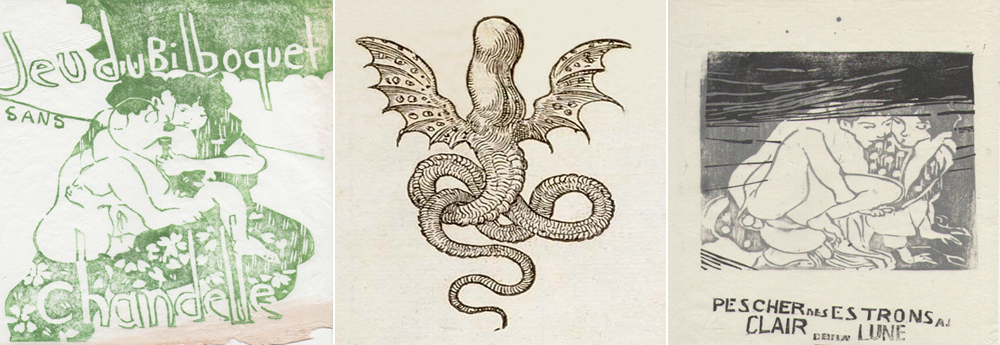

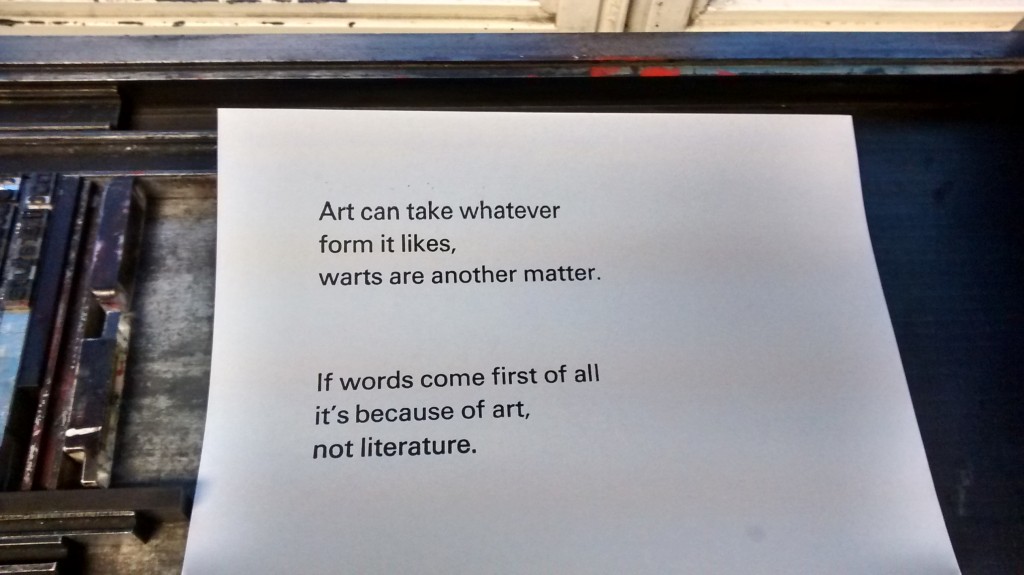

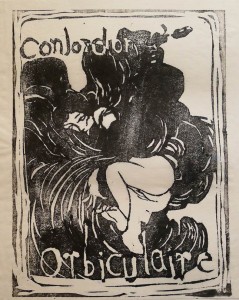

The proverb, ‘quiconque a belle femme tout le monde est son cousin’ (literally ‘whoever has a beautiful wife, everyone is his cousin’) encapsulates the happy fate of the cuckold and his horns of plenty, gifts that keep on giving, rather like Bruscambille himself, who seems to have been the first to have recorded this piece of wisdom in print, and which has now inspired Dominic Hills’s latest two-stage print: